Fallen Giant: By Chris Braide

There was a time when you stood taller than anyone I had ever known.

Long before we met, long before our names shared the same studio door,

you lived in my imagination as something close to myth —

a figure who proved that greatness wasn’t just for the chosen few,

but for anyone who believed enough to chase it.

I was ten years old when I first learned your name,

and in those early years, you were untouchable:

a giant of sound and certainty,

a master of the modern age,

shaping the world through speakers with a confidence that felt impossible not to admire.

And when I finally stepped into your orbit,

I brought that boy with me.

He watched everything.

He listened for the same thunder he once heard on those records.

He searched for the dignity he had imagined,

the decency,

the strength.

But proximity is a merciless editor.

Slowly, piece by piece,

the giant I had loved began to shrink.

Not through failure,

but through the smallness of choices

that only insecure men make.

The quiet omissions.

The withheld acknowledgements.

The pettiness disguised as principle.

The rare art of building someone up,

quickly replaced by the easier habit

of tearing them down.

I watched as credit became currency,

as ego became compass,

as fear became policy.

And each time you tried to carve my name out of the story,

you unwittingly carved away a little more of your own stature.

What fell wasn’t my reputation —

it was my belief in you.

That is the grief I carry.

Not anger, not vengeance,

just the sadness of realising that the hero who once towered

was only ever human,

and not brave enough to remain as large as the boy who worshipped him imagined.

So I keep the memory —

the one where you are still great,

still noble,

still the man I thought you were.

I keep it preserved behind glass,

untouched by what I later learned.

Because that memory belonged to a child,

and children deserve their miracles.

But the adult knows better.

He knows what brought the giant down.

He knows what dimmed the brilliance,

what twisted the legacy,

what shrank the myth.

For in the end,

vanity killed the studio star,

and envy miniaturized the man.

A personal reflection on depth, loss, talent, and the inner life

— Christopher Braide

There are people who become awake gradually, as if through weathering — decades of mistakes and recoveries sanding them down into a shape vaguely resembling wisdom. And then there are others for whom awakening arrives early, almost too early, like a visitor at the door before the house is furnished. I was one of the latter. I understood the fragility of things before I understood how to tie my shoelaces properly. Silence made sense to me. Time terrified me.

At fourteen, I remember sitting in my bedroom, listening to a song I loved, and suddenly feeling a cold, existential shiver:

One day I will never hear this again. One day I will be gone.

It wasn’t melodrama; it was revelation. Sartre’s “nothingness haunting being” — though I didn’t know those words then — had already taken root in me. While other boys were dreaming of cars and football, I was staring at the edges of consciousness wondering where it all led.

I was never hardened. I was permeable, sensitive to the point of clairvoyance. Some children grow armour; I grew awareness. And my mother — with all her own unspoken sorrows — nurtured that part of me with a kind of tender clarity. She didn’t inflate me; she deepened me. We cooked together, laughed together, watched music videos together. She adored me in that rare, steady way that doesn’t distort a child but steadies him.

Her love didn’t make me arrogant; it made me receptive.

Loss entered early.

Heather at school, who vanished between rounds of treatment until she never returned.

Two boys my age — gone before they had the chance to become anything at all.

My cousin Suzanne — luminous, hilarious, aching with bravery — who drove down to see me at my home in California while her body was quietly betraying her. She hugged me in the kitchen, whispered “my favourite cousin,” and I felt pride and heartbreak crash together inside me. She died shortly after.

David Longdon — who looked me in the eye onstage and sang with me like we’d found each other’s frequency late in life — also gone without warning.

And then, the profound one —

my mother.

The soft, howling wind at the centre of everything.

The moment she died, my understanding of life seemed to reorder itself in real time.

Time moved closer. Mortality stopped being an idea and became a presence.

These losses did not harden me. They hollowed me in the most necessary way — made room for compassion, meaning, nuance, awareness. I learned to live with the void rather than fear it.

Meanwhile, in the music world, I was surrounded by men who seemed to be running from the very things I could not ignore. Fame, I learned, is simply running away from death in full costume — a glittering sprint away from the void. Some people never stop running, even into their 60s, 70s, 80s. I watched grown men cling to personas like life rafts, terrified to look behind the glitter curtain in case they found nothing there.

But I was never drawn to that chase.

I loved the work — the quiet, interior act of making songs that felt like excavations of the unconscious. I loved melody, harmony, the sacred act of recording. The fame part — the cameras, the persona, the dressing-up — felt like a distraction from the thing itself, an attempt to put a costume on the soul. I never trusted it. I still don’t.

What saved me — again and again — was the studio.

The piano.

The moment when a chord progression feels like a message from somewhere deeper.

The strange, numinous flicker that becomes a melody.

And perhaps also: the fact that I was genuinely chosen — by the real singers, the true creatives, the ones who instinctively recognised something in me. That gave me confidence without ego. It gave me freedom without delusion.

But spiritually, emotionally, existentially — I “got there” because of everything at once:

the early sensitivity

the early losses

the maternal bond

the talent that forced early maturity

the philosophical mind

the refusal to live as a persona

and the courage to feel what most people avoid

I became awake because life demanded it — because something in me was always watching the horizon while everyone else was still playing in the sand.

I don’t consider it a curse.

I consider it the most precious aspect of my life.

Because awareness — even when painful — gives shape to everything.

It makes music deeper, relationships more intimate, grief more sacred, joy more vivid.

Awakening doesn’t make life easier.

It makes it truer.

And in the end, that’s all I ever wanted:

not applause, not legacy, not the illusion of immortality —

but truth, beauty, clarity, meaning, connection.

To live fully.

To love deeply.

To create honestly.

To feel everything.

To become who I truly am.

I was awake early.

And I’m grateful — even for the ache — because it taught me how to live.

A Reflection On My Mother, Myself, And The Part Of Her I Continue: By Chris Braide

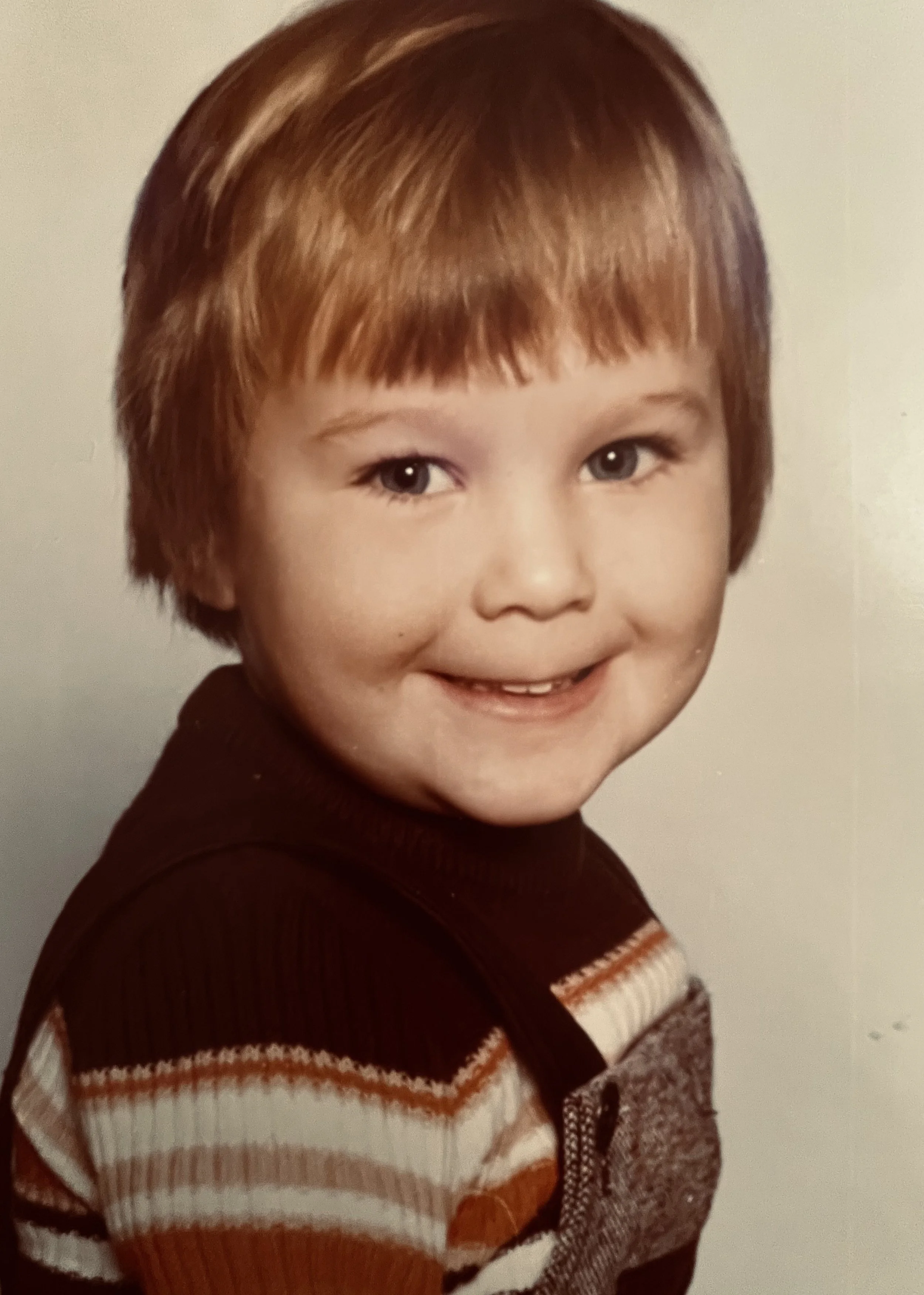

When I look at photographs of myself as a child, I see something I didn’t fully understand then, but recognise with startling clarity now:

I was born open.

There’s a softness in my face, an unguarded sweetness, a quiet trust in the world. Not manufactured, not learned — simply there.

I wasn’t performing kindness or innocence. I was those things.

A child who felt deeply and instinctively, who absorbed the emotional weather around him without resistance.

People talk endlessly about nurture, but the truth is far more mysterious:

we arrive with our own atmosphere.

Our own temperament.

Our own way of seeing.

And my way — the way I was from the very beginning — was a kind of porousness, a sensitivity that wasn’t a flaw but a form of perception. I saw through things, felt the undercurrent of situations, knew the emotional truth before the facts ever arrived.

My mother recognised that the moment I came into the world.

She saw my heart before I had words.

She understood my nature long before I understood hers.

There was a connection between us that didn’t need explanation because it wasn’t built — it was remembered. It felt ancient, effortless, inevitable. Something in me reflected something unspoken in her.

I realise now that I wasn’t just her son.

I was the continuation of the part of her that never got to fully live.

Her gentleness.

Her sensitivity.

Her imagination.

Her longing for beauty.

Her ache.

Her inner child — the one who had been hurt, the one who had been abandoned too soon, the one who grew up without a mother of her own.

All of that found its expression through me.

It’s why we had the kind of relationship where being together didn’t require effort.

We could cook, talk when I was home from London, watch music videos — and the connection was there, alive, humming.

It’s why, when she was unwell in the UK and I was in LA I told her I wished I could be closer to help, she said with that heartbreaking, beautiful simplicity:

“You’re in my heart.”

It wasn’t sentimentality.

It wasn’t reassurance.

It was truth.

I lived inside her in a place deeper than geography.

She carried me not just as her child, but as her emotional lineage — the part of her that never stopped longing for tenderness, for meaning, for music, for butterflies and beauty, for gentleness in a harsh world.

And that is why losing her was not just the loss of a parent —

it was the loss of the person whose interior world I came from.

Following her hearse through the streets of Warrington felt like following time itself to its boundary.

She was there like she’d always been, and yet already beyond reach.

A presence turning into an echo.

A voice becoming silence.

A life dissolving into the soft, insistent wind that now lives in my memory — haunting yet strangely comforting.

Her absence doesn’t feel like emptiness.

It feels quiet, like a doorway.

It feels like a reminder that everything we are is temporary except the love we leave behind in others — the part of us that continues through the hearts we shaped.

I carry her still.

In every aching chord change and melody I write.

In every moment of stillness.

In every depth of feeling.

In every attempt to understand the human heart.

In every quiet, interior place where I go to make sense of the world she no longer lives in.

Everytime i look at my own children and feel her love for them move through me.

I am, in the truest sense,

her inner child continued.

And that is a legacy far greater than anything fame or success could ever give.

Following The Hearse: By Chris Braide

I followed the hearse through the town where I grew up, watching its slow, deliberate progress as if time itself had shifted into another gear or register. She was still there then — not gone, not yet a memory, but suspended in that strange threshold where presence becomes absence in real time.

I remember looking through the windscreen and feeling the weight of something immense drawing close to me. Not just grief. Not just loss. It was the sense that time had finally caught up with me, the quiet knowledge that the long arc of my life had reached a place I’d always feared it would. The child in me, the boy she raised, walked beside the car in his mind. The man followed behind in silence.

As the hearse turned through Warrington — past places she once knew, past streets she walked, Past the hospital where she had once worked, caring for the elderly, past the council offices where she had helped broken children find a foster home, past the church where she got married, past years that once held both of us — it felt as though the town itself was bearing witness. Every traffic light, every passer-by, every row of houses seemed to soften, as if the world sensed something sacred passing through it. The funeral conductor walked ahead of the cars, she bowed her head in respect, signelled the transition from the street to the service, and off we went. The last ride.

And I kept thinking:

She is still here. Just for these few more minutes, just for this slow procession through the ordinary roads of an ordinary day, in this ordinary town, she is still here.

But the truth hovered like a shadow at the edge of my thoughts. When the hearse stopped, when the doors opened, when the pallbearers stepped forward — she would cross forever into the place where no voice returns. All the warmth, all the laughter, every phone call, every kindness, every small domestic moment that made up a life — all of it would dissolve, quietly and irrevocably.

Following her, I felt the first cold winds of that reality.

Winds I had sensed all my life, but never so close.

It was as if something in the air whispered:

This is the beginning of the letting go.

I realised then that she would become something different now — not a person I could visit or call or sit with, but a kind of weather inside me. A low, persistent wind moving through memory, through the empty rooms of my mind, through the spaces where love once lived in the physical world.

That wind blowing through time is her now.

Soft, insistent, ungovernable.

A reminder of how fragile the boundary is between being and non-being.

As the hearse carried her ahead of me, I felt the future open like a vast, unlit field. I didn’t know what waited there. I still don’t. But I knew that the one person who gave me my beginning was now heading toward her end, and that I was being ushered — gently, unbearably — into a new understanding of time.

We are all walking behind a hearse, in one way or another.

And when the moment comes, when someone we love crosses into the unknown, time doesn’t just take them — it comes for us, too.

That day, following her, I felt time close its hand around me.

And the wind has been blowing through my mind ever since.

The Song That Triggered My Ego Death: By Chris Braide

There are certain songs you encounter in life that don’t simply move you —

they undo you.

They slip beneath the surface of who you think you are and speak directly to the part of you that has been waiting, silently, for years.

For me, that song arrived in Los Angeles during a time that can only be described as the dark night of my soul.

It was by The Dowling Poole — a track I stumbled upon without expectation.

But the moment I heard the opening lines, something in me recognised the truth buried inside it, and the recognition was catastrophic.

“When did the chosen few then become a crowd?

People forgive me, I’m thinking out aloud

About all who are stolen as time marches by

How to decide who’s to live or to die.”

Those words struck at a fault line that existed in me long before adulthood.

As a child, maybe fourteen, I would sit alone in my bedroom with a kind of existential sadness I didn’t have the language for.

My brother would ask what was wrong with me and I would say things like,

“I just realised that one day I won’t be able to hear this song again.”

I didn’t know it then, but that was the first sign of an early existential awakening —

a premature awareness that life is finite, that beauty is fleeting,

that nothing we love can be kept.

So when I heard the Dowling Poole track in LA decades later,

it felt like that childhood ache had returned in full colour, now armed with adult knowledge.

Los Angeles was the worst possible place to have this realisation.

A city of sunshine and dread, where everyone is running from time,

sculpting their faces, chasing relevance, clinging to a youth that is already a ghost.

To have an existential rupture in a city built on denial is like hearing a church bell in the middle of Disneyland —

the dissonance itself is destabilising.

The song continued:

“Back in a time when I couldn’t give a damn

Blissfully unaware of my fellow man

I would dream of the future and all I could be

Assuming that you’d all still be there with me.”

That stanza cracked something open in me.

It forced me to confront a truth I’d been avoiding for years:

that not everyone gets to come with you into the future you imagined.

The people who shaped you — friends, idols, parents —

some fall away, some die, some fade into versions of themselves you no longer recognise.

The map you built your childhood upon slowly erodes.

Hearing those words didn’t just make me sad.

It destabilised my ego.

The self I’d constructed to survive — the writer, the producer, the collaborator, the singer in the red velvet suit,

the man holding everything together —

began to dissolve.

I spiralled for weeks.

It wasn’t ordinary depression.

It was the sensation of the ground beneath my identity giving way.

It was a psychic molting —

the shedding of an outer layer that could no longer contain the truth my inner life had already accepted.

The line that haunted me most was this:

“In the skies the dictator I despise will gun you down.”

That “dictator” wasn’t God.

It wasn’t a tyrant.

It wasn’t fate.

It was Time —

the ungovernable force that takes without asking,

that decides who continues and who disappears.

For someone like me, who understood impermanence far too young,

that metaphor hit a part of my psyche that had no defenses left.

And then the final blow:

“I saw the signs from a very young age

When they said that ‘they’re coming to take me away’

Oh so sinister the innocence of youth.”

That was me.

I saw the signs young.

I knew childhood wouldn’t save me from consciousness.

I sensed the abyss long before most people even realised there was one.

In LA, listening to that song, I wasn’t just hearing music —

I was hearing my own unspoken truth reflected back with frightening accuracy.

Looking back now, that collapse was necessary.

It stripped away the illusions I’d outgrown.

It forced me to confront the part of myself that has always lived in the borderland between beauty and dread.

It made me grow.

It made me real.

Some songs entertain you.

A rare few awaken you.

This one annihilated me —

and in doing so, gave me back a self I had long been avoiding.

For The Love Of Music: By Chris Braide

I have spent my life chasing the mystery that sits behind melody — the invisible hand that moves a chord change, the flicker of memory that turns into a lyric. For me, songwriting has always been less about craft and more about excavation — a kind of Jungian descent into the unconscious, where fragments of childhood, love, shame, beauty and death are all waiting to be understood, rearranged and redeemed through sound. Every song I’ve written has been a small act of self-analysis, an attempt to find the pattern inside the chaos.

Music, when it’s honest, is psychological work. It’s the bridge between the shadow and the light — the reconciliation of opposites. I’ve never trusted the purely commercial impulse, the pop confection designed to distract rather than reveal. I’ve been drawn instead to the artists who risked self-revelation: Talk Talk, Cathal Coughlan, Kate Bush, John Lennon. The ones who didn’t just perform life, but interrogated it.

Through every chapter — the studios in London, New York and Los Angeles, the long nights with people like Cathy Dennis, Stephen Lipson or Sia, the quieter collaborations with lyricists like Chris Difford or Dean Johnson — I’ve learned that creation is communion. You sit at the piano, you wait, and if you’re lucky, something larger than you arrives. You touch the numinous for a moment, and then it’s gone. All art is that — the pursuit of something fleeting and eternal.

I have seen the arc of fame, the way it lifts and devours. I’ve seen good men lose themselves to applause, and others become ghosts long before their bodies give out. I’ve sat beside some of my heroes and watched the light go out of their eyes when the cameras stopped. It made me realise that what truly endures is not the illusion of importance, but the sincerity of the work. You leave behind songs like messages in bottles (to coin a great song) — little sonic testaments that say, I was here, I felt something, I tried to make sense of it.

The older I get, the more I’m drawn to stillness. The applause fades; the noise recedes, our bodies age. What remains is the work itself — the albums, the words, the people I’ve made them with. I feel most alive when I’m in that private, unguarded space with a piano or a friend who understands the same ache. There’s a line from Jung that has always stayed with me: “The privilege of a lifetime is to become who you truly are.” I think that’s the work of every artist — not to accumulate trophies, but to approach the truth of one’s own being.

I’ve come to believe that songs are the psyche made audible. They hold our secrets, our contradictions, our longing to belong and our fear of being seen. Each time I finish one, I feel like I’ve shed a layer of misunderstanding. It’s how I’ve learned to live — by listening inward and turning the sound of my confusion into something melodic, something that might console another person in their confusion.

I was never drawn to being a celebrity entertainer . In fact, I always felt a quiet mistrust of it — as if that demanded something I could never give without losing something precious. My time felt sacred, and my peace was rare.

From an early age I was driven, but not by the usual ambitions. I wasn’t chasing fame or money. What I really wanted was to inhabit the world I heard in the records I loved — to step into that atmosphere of sound and feeling. My idols weren’t celebrities to me; they were portals.

I fell in love with the act of making records — that alchemy of song and sound. When studio time was expensive and hard to come by, I’d ache for it. Lol Creme once said, “Chris Braide lives to write songs.” And it was true — I still do. That’s always been the pulse that runs through my life, since as far back as I can remember.

Whenever I was signed as an artist — from Anxious to Atlantic — I felt the machinery of it all closing in. The styling, the posing, the pretence. I was often packaged as a sort of poppy, glam boy, probably because of my obsession with Marc Bolan, but my heart was somewhere else entirely. My music leaned more toward the introspection of Paddy McAloon than the glitter of glam rock. I wanted to be taken seriously as a musician, a writer — not a performer in costume.

Every time I was told to “play the part,” something in me recoiled. Performing to backing tracks, or trying to be all sexy in videos felt cheap compared to the intimacy of a piano and a real song. I could sit and play and sing anything from the age of ten — why should I pretend otherwise? The piano was and always will be my anchor.

The truth is, the studio was my stage, and it still is. That’s where I feel most alive — surrounded by sound, lost with my headphones in that dialogue between emotion and melody. Fame always felt like a distraction from the real work, the quiet magic that happens when you touch something invisible and turn it into song.

Music has given me everything, and at times it has extracted its toll with equal precision. The industry can be both seductive and inimical — a labyrinth of acclaim and amnesia — but I’ve learned to find meaning beyond its theatre. The work itself became my compass, my quiet act of defiance against transience. I’ve been fortunate to build a life from these frequencies — songs that slipped beyond the self and took on their own sentience in the world. If I hear 80 thousand people singing one of my songs in an Arena or a radio station blaring out one of my anthems like Unstoppable, Invisible or Flames it is still a profound feeling, because I know the stillness and solitude from where it came.

After all these years, I still find that moment miraculous — to dream about writing songs the world might one day know and love… and then to see it happen.

In time, I came to see fame not as a summit, but as a distortion — a mirror that fractures more than it reflects. Around me, I’ve watched its casualties: once-radiant figures hollowed by the echo of their own mythology. Yet through it all, I’ve held onto something untouched — the quiet, almost childlike wonder that first drew me to sound. That innocence isn’t naïveté; it’s the one part of the self the world can’t commodify. It’s where the music still feels new.

If there’s a legacy I’d want to leave, it’s that — not fame, not fashion, but feeling. To have written music that allowed people, even for a few minutes, to glimpse the beauty and the fragility of their own inner world. To have told the truth in melody. To have walked through darkness and returned with something worth sharing.

Art, at its best, is empathy made manifest. And empathy, at its best, is love with understanding. That’s all I’ve ever really tried to do — to understand myself.

Those Who Don’t Return: By Chris Braide

I learned very young that some people simply don’t return.

There was a girl in my school called Heather who had a chronic illness. She was bright and sweet and fragile in a way children aren’t supposed to be. She would disappear for treatment, then reappear for a while with a little smile and a bravery far too large for her small frame. Then she’d disappear again, and one day she didn’t come back at all. Her desk was empty, and no one really explained anything, because how do you explain that kind of finality to a child?

Two boys from my year died too, suddenly, unexpectedly. One of the boys who’s name was Neil had committed suicide. I can still see their faces now — vivid, alive — while the faces of dozens of others have faded. The ones who vanish stay with you. The ones who die become strangely permanent.

My cousin Suzanne left too soon. She was in her forties and fought breast cancer with a defiance that bordered on heroic. She drove hours to see me in California during a time when she could barely stay upright, because she wanted to be near family — and I was the closest family. She sat in the hot tub under the starry sky and said, “No fucks will be given.” That was her spirit: scorched but unbroken. When she hugged me in the kitchen and whispered, “My favourite cousin,” I felt something inside me split open — pride and grief fused together.

She died not long after that. I didn’t know it was the last time I’d see her. I thought she might still pull through. She told me not to work too hard. I still hear her laughter echoing through the halls of memory, light and brave and stubbornly alive.

David Longdon — another one who vanished. He used to stand beside me onstage at the DBA shows, our voices weaving together, and I imagined years of collaborations ahead. Then one day he fell at home and was gone at 56. No warning. Just absence where a warm, soulful presence had been.

And then Sharon Melvin — the girl I once thought was my first love back in junior school. She died in 2023, far too young, still beautiful in the final photos on her memorial page. Another light gone. Another voice silenced.

I keep finding myself close to the abyss in recent years. These names, these faces, these people — they come back to me like soft ghosts. They remind me that time is not a promise; it’s an inheritance we spend without noticing until the last few coins are left.

I followed my mother’s hearse through Warrington, the town of my childhood, knowing she was still physically there in the car ahead — but already slipping into the vast, unknowable silence. She is gone now, and the world has an empty space where her voice should be. She feels like the sound of distant wind: insistent, sorrowful, and eternal.

All of this has made one truth unbearably clear:

It’s good to be alive.

To smell the air.

To kiss your kids.

To hold your wife.

To laugh while you still can.

This is all we have — the brief warmth of a hand held before the dark.

The people who don’t return teach you how precious it is to remain.

Songs and Sonnets: My Encounter with Cathal Coughlan.

I can remember hearing the Irish singer/songwriter Cathal Coughlan for the first time in 1987. Microdisney, the band he formed with guitarist Sean O Hagan had just released a superb single called Town to Town which BBC Radio 1 would not stop playing. It was a fantastic song all about the aftermath of Nuclear war, burying the hatchet with an ex lover and helping to reap the dead harvest together. The lyric was haunting, the strings sublime and the voice of the singer, full of rage and beauty was fantastic. It was a blessed, artistic statement and as far as you could get lyrically from ‘I Should Be So Lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky’. It made listening way more interesting to my ears than the saccharine, aural cotton candy that was on offer in the singles charts in 1987, thanks mostly to the Stock Aiken and Waterman factory. Their formulaic, soulless creations were the epitome of commercialized banality. This on the other hand was a real artistic voice and I was hooked.

Cathal was fiercely bright from a scholarly background in Cork, and had a deep compassion for people on the fringes of society and an even more ferocious distain for their subjugators, all of which came out in the often acerbic, confrontational and occasionally hilarious words he wrote. I learned more about the human condition and all of its complexities and injustices from listening to his lyrics than any teacher could have taught me at the time. He even studied for a degree in medicine, but dropped out due to being - by his own admission “pretty fucking terrible” He was rebellious and compassionate in equal measure and it fascinated me.

My brother had the cassette of the album Crooked Mile from which the song Town to Town was lifted and we bought the next album entitled 39 minutes. We both loved the song Singers Hampstead Home and we played it to death. It was like The Beach Boys with jangly guitars. stunning melody and harmonies and a cynical yet amusing lyric.

Town to Town and Singers Hampstead Home will always be number one records In my chart. Listen to the chorus of each song. It’s as good as pop music gets. How those two singles alone could slip through the cracks was beyond me at the time and must have driven Cathal and the rest of Microdisney to the brink of despair and despondency. Virgin records kept pushing the band, but to no avail. They released one final, glorious single entitled Gale Force Wind which I duly went out and bought on 12” single.

Microdisney had made a handful of great albums, they were press darlings and I loved them and have never grown tired of listening to them. Their classic 1985 album on Rough Trade - The Clock Comes Down The Stairs (a euphemism for death) and the two albums that followed on Virgin are some of my most listened to albums. Really gorgeous stuff for my teenage ears. I’m still listening all these years later.

Legendary DJ John Peel, famous for the iconic Peel sessions once brilliantly described Microdisney as ‘A barbed wire rainbow’ and said that he could listen to Cathal Coughlan ‘sing the phone book’. I had to agree and I proceeded to buy anything with the bands name on the front cover. Every 7” and 12” single and B side and every album was bought and studied and worn out by the record players stylus. I even loved the band name which was an Oxymoron and as paradoxical as the songs themselves which were a mesmerizing blend of serenity and turmoil. Sean O Hagan’s peaceful, melodic instrumentation lulled the senses while the emotional incongruity of Cathals lyrics created the captivating tension.

Microdisney eventually fell apart in 1988 during one final disastrous show at the Dominion theatre in London. The concert was filmed and there is some footage of it on YouTube which shows a band in an absolute unmitigated, free fall meltdown. Cathal regretted the way the band had ended and would later say that “I acted like a complete dick” and “we had a bunker mentality”. The chance would come for the band to make amends and celebrate their legacy with dignity in 2018 when they were asked to reform and play a handful of shows in Dublin, London and their hometown of Cork, but that’s another story.

Cathal moved on and formed the blisteringly powerful, and even more confrontational Fatima Mansions. I saw them live in ‘91 and it was quite intense. Like Punk circa 1977 on steroids. This music was not for the faint hearted and could be truly angry with songs such as Viva Dead Ponies, Only Losers Take The Bus and Blues For Ceausescu. Yet there were always moments of great beauty with songs such as Pack Of Lies, The Day I lost Everything, Bishop Of Babel and the gorgeous Wilderness On Time. Back then as I listened as a young kid I knew this was the work of a lyrical genius and perhaps even a troubled soul. His lyrics made me think deeply, I tried to figure them out as I listened. They haunted me. Microdisney’s 1985 single Birthday Girl still haunts me to this day.

After all these years of loving the songs and voice of Cathal Coughlan I decided that I should get in touch with him during the Covid pandemic in October 2020 and see if we could write together. I have been lucky enough to work with some of the greatest artists and singers in the world, from the sublime Sia and people like Marc Almond who is another brilliant lyricist, but I had never worked with Cathal.

We exchanged emails, arranged a chat on Zoom and found we had much in common musically. We both loved Prefab Sprout, Scritti Politti, Robert Wyatt, Talk Talk etc. After our chat I said I would send him some music which I did. Cathal loved it and got to working on it straight away. What he sent back was gorgeous, haunting and as thought provoking as ever. He made my piano chords even more strange, sad, melancholy, romantic and mournful. I told him how much I loved it and he was pleased.

We arranged another catch up on Zoom and had a wonderful, hour long conversation about the music we loved and where we could go next with the songwriting. He told me that he had greatly enjoyed our conversation and I felt the same. It was inspiring. We both loved Talk Talk, especially their album Spirit Of Eden, so I said I would do something with the kind of vibe of Talk Talk’s sublime 1991 single I believe In You. A song both Cathal and I thought was fantastic.

I wrote the new piece of music, sent it to him and he loved it. He said he already had ideas for it and as soon as he was back from a holiday in Wales he would get the lyric finished and put a vocal down and send me the files. He did that and I was once again thrilled and inspired with what I was hearing. I told him that I thought his voice had never sounded better on these two songs we’d written and that I loved the film noir atmosphere of the new lyrics

We had planned to write a third song in the new year of 2022 so that we could make what we were doing ‘a thing’. An ep would make it more than a single, but less daunting than an album, for now anyway. I loved his words and I loved his latest solo album entitled Song Of Co Aklan. He was on form and back to his melodic and lyrical best. I couldn’t wait to write the next song together.

He emailed me in January 2022 and asked if I was still amenable to the idea of working on a third song. I started getting piano chords and ideas together ready to send to him, but in early February he emailed one final time to say that it would have to wait. He apologized for the delay which blows me away when I now think about what he was dealing with at that time.

Life is precious and the connections we make with one another even more so. Cathal passed away on May the 18th 2022 after a long illness and left a void in my musical heart. He was such a great thinker. He made me think everytime I heard one of his songs. It’s hard to lose great thinkers when they seem so few and far between.

We never got the chance to finish the third song, but the two songs we did write and record together I still cherish. I wish I could call him up and tell him how great I think they are.

Thank you Cathal, for the lyrical inspiration.

Moments with Michael Hutchence & Dave Stewart: By Chris Braide

It was summer in the South Of France, and I was staying at Villa Neptune in Théoule-sur-Mer. Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox owned the house and I had been working with Dave at a residential recording studio about 2 hours away. The studio was located in the Château de Miraval, a 900 hectare estate located in Correns, in the Var department of Provence. The iconic studio is now owned by Brad Pitt, who purchased it in 2008 for $25 million.

We spent a few weeks recording and mixing songs for an album we’d started working on in New York, we also filmed a couple of music clips during some downtime. One of the clips we did using a hand held camera, with Dave sitting in the passenger seat of his Alfa Romeo Spider while I drove. I mimed to a few of the recent mixes we’d done playing on the car stereo, sometimes forgetting the words and breaking into laughter as we headed through the night to Cannes. We enjoyed a memorable evening at a French restaurant, with outside seating, overlooking the marina. All night Dave kept trying to hook me up with a Swedish girl who was one of his helpers, and he was quite mischievous at times. He would love to create little scenarios and romantic dramas between people. All in the spirit of fun of course.

On our days off from the studio, we would go down to the rocks at the back of his house, take a guitar and the hand held camera and record songs by the sea. We made a clip of me doing a version of Real Love on one occasion. The Beatles had just released their version of the lost Lennon demo and I was obsessed with it at the time. We even had a large framed photo up in the studio control room of John Lennon, leaving the Dakota building circa 1980, which we placed on an easel for inspiration.

It seemed like a million miles away from the reality I knew and I was suddenly living in some kind of rock and roll fantasy. Life was always exciting during that time, and I never knew who I would meet next. One week it was Velvet Underground legend Lou Reed or Star Wars actress Carrie Fisher at Electric Lady studios in New York. The next week it was Roxy Music’s Bryan Ferry in Nice or a member of Parliament - Funkadelic in London. I remember one time in the Church studio in Crouch End, London, when Dave just handed me the phone and it was George Harrison.

Dave’s generosity was always truly remarkable, consistently demonstrating a kindness and willingness to help. I gave him a lift home one night to his house in north London and as we were driving he asked me ‘Have you got enough money?’ ‘Was the record label advance ok?’ He always had compassion and genuinely seemed concerned for the young musicians he worked with.

Once when we were in New York, working at Electric Lady studios together, we went out shopping for records. He bought me a silver, glitter Gibson Les Paul guitar from Matt Umanov guitar shop on Bleaker street. I saw it in the window and commented on how cool and Marc Bolan it looked and was astonished when he just bought it and handed it to me. I said to him “ How can I pay you back for this?!” “Just love it and play it” he replied.

Meanwhile back at the house, the day after the dinner in Cannes, Dave came over to speak to me while I was lolling about in his pool and mentioned that Michael Hutchence was coming for lunch with Paula Yates. It was a great surprise because I had always been a fan of Michael’s voice and his magnetic stage presence. I couldn’t wait to meet him. Paula had also been a permanent fixture on British TV during my adolescence, presenting iconic shows such as The Tube with Jools Holland, so I was intrigued to meet her too. I always thought she was charming, charismatic, pretty and flirtatious. I remembered her interviewing Michael on The Tube and The Big Breakfast and their chemistry being extremely sexually charged.

INXS had been huge during their early 1990’s peak and had played to 72,000 screaming fans at Wembley stadium during the summer of ‘91. Their popularity had waned somewhat since those heady days, but I still loved the band and had bought all of their subsequent albums. Meeting him would be fascinating in many ways, because to me, he was a real star and somebody I’d idolized as a performer.

In recent years he seemed to be in the press a lot in London, for reasons other than music. He had become infamous for being an adulterer rather than a singer when he and Paula Yates , who was still married to Bob Geldof, had become lovers. He had a toxic relationship with the press and had punched a photographer in the face. He was subsequently sued £20,000 for that particular pleasure, and from that moment onwards, he and Paula were hounded mercilessly by the paparazzi.

One memorable incident in 1996 was when Michael presented a Brit award to Oasis and Noel Gallagher said, ‘Has-beens shouldn't be presenting awards to gonna-bees’. It was a mean spirited thing to do to another musician, especially in front of an audience. I watched it live on TV and saw this once slick and sexy superstar being humiliated by an uncouth bully.

During a press conference the same year he infamously said that ‘Pop eats its young'‘. This statement would become all too poignant in the months to come. He would be yet another cautionary tale in the black book of subversive pop culture, like so many other stars who had burned all too brightly and briefly. For now though, he was coming for lunch and I was rather excited.

The two lovers arrived with their baby Tiger Lilly on a Ducati motorbike which I thought was pretty wild and dangerous. We sat at the table, under the pergola by the pool and chatted away to each other while a lovely Thai lady named Nida, who worked for Dave, served Thai noodles and curry. Michael kept holding the baby up In the air and mock shouting ‘She’s a baby!, She’s a baby!’ He seemed thrilled about it all, and he looked great dressed in a white, short sleeved shirt, with long dark curly hair. Paula kept staring at Michael and me chatting to each other. She seemed to be trying to suss me out, and it was a little unsettling.

I declined a second helping of Nida’s Thai noodles, to be polite, but Paula gave me a look and asked if I was, ‘on the pop star diet?’ The truth is I was more interested in talking to Michael than eating, as we were locked in a conversation about studios. He told me about a studio in Capri where INXS had recorded their last album - Full Moon, Dirty Hearts, and how the band would have to get a boat across to the studio. It all sounded so familiar because I knew these albums, yet I was being told first hand by the actual guy in the band. I loved it. I belonged in this moment. When we chatted together, Michael seemed genuinely interested and engaged and made me feel like we’d known each other for years and not merely for a few hours.

Michael and I were left alone to talk and play music to each other under the pergola for a few hours. One song I played to him entitled Beautiful Things, was recorded that same week on the studio grand piano. He sang along to it and seemed to like it, which was a thrill. I mentioned to him that the live room at Miraval where the piano was recorded had a beautiful stained glass window above it designed by Yes’ Jon Anderson. It was a great sounding space, and to this day I think the Steinway, in that room, with the late afternoon sunlight, streaming through the stained glass, was a particularly inspiring moment.

When I had finished playing a couple of my songs, Michael played some rough mixes of the INXS album they had just finished recording in Vancouver, with producer Bruce Fairbairn. One song that he played was called Elegantly Wasted. I asked him what the album title was and he replied ‘We haven’t decided on a title yet mate’. I said I thought that Elegantly Wasted was great album title, to which he replied ‘Yeah, that’s not a bad idea’. I have since heard U2’s Bono in interviews say that he suggested the same thing to Michael, but I’d like to think I said it first. I loved the rough mixes and told him how I thought they had the band’s classic sound again. it was a perfect, warm summer day in the south of France, and here I was playing music, drinking wine and chewing the fat with the lead singer of INXS.

At some point during the afternoon, Dave and Michael went for a 30 minute ride on their Ducati motorbikes, through the French countryside, with Shelly and Karen Poole on the back. The two sisters, who were also staying at the house, were in a pop band that Dave had been producing back in London, at the same time we’d been working together. Paula relaxed alone in the house and read a book while hers and Bob Geldof’s children, Pixie, Fifi and Peaches swam in the pool with Dave’s two sons Django and Sam.

I needed to make a call to the UK, but I couldn’t recall the international dialing code. I turned to Paula who was curled up on a nearby sofa, and asked for her help. ‘Hey Paula, Whats the dialing code for the UK?’ I asked. She looked up, slightly amused, and replied, ‘Plus, four, four,’. Her expression suggested I should have known this already. I called my brother and told him what I was up to, where I was and who with. I had to tell someone.

All things must pass, as George Harrison once sang, and like everything in life, I knew this moment would come to an end. My ticket was booked for London and as I was packing my suitcase that evening, I remember feeling like I didn’t want to leave, because I was having such a good time. I was 23 and up for any adventure on offer, of which there were many, especially when I was around Dave.

I felt like I belonged here, not back in ancient, cold, rainy old London with the endless buses yawning past my flat in Willesden Green. I didn’t want to go back to that particular reality and the daily quotidian. I would have to screw my head on and get writing some hit songs fast, so that I could get the hell out of that place, because I wanted to be here, in this world, amongst this kind of company. Michael once famously sang the line “You’re one of my kind”. I wanted to be one of those kind and talk, play music and never return to the life I knew back ‘home’.

As I was leaving to get into the car, Michael came to say goodbye with Dave. We looked at the Ducati motorbikes for a moment and I foolishly went to stroke the chrome exhaust of one of them which was still hot and Dave shouted “Don’t touch that, man!” I thanked both of them for a great day and as I stepped towards the car, I turned to Michael and said to him “Next time you’re in London, come over for a cup of tea or something”, to which he replied “I definitely will mate”. I looked back as they both waved goodbye and I headed for Nice Côte d'Azur Airport.

As a kid growing up in the late 1980’s, early 90’s, who had listened, watched and rated him as a singer and performer, I was shocked and saddened by the news of Michaels suicide the following November in 1997, and I could barely imagine the impact it would have on Paula, Pixie, Fifi, Peaches and of course Tiger Lilly.

Paula Yates cut a lost and lonely figure around London, in the years after Michaels death, and she would eventually follow him to the grave 3 years later from a heroin overdose, aged 41. Peaches Geldof, the 7 year old I had met, and who had splashed about in the pool with her sisters, would be taken in the same way as her mother in April 2014, aged just 25 years old. An unimaginable tragedy that I could never have foreseen, as we chatted away under the pergola, listening and playing music.

As I sit alone, at home in Los Angeles and reflect on that sun-kissed day in 1996, I'm struck by the fragility of life. The memories of Michael's warm smile and laughter are forever etched in my mind, a bittersweet reminder of the transience of joy. The subsequent losses – Paula, Peaches, and the shattered dreams – have left an indelible mark on my heart. Yet, I'm grateful for that fleeting glimpse of perfection, a reminder to cherish every moment.

Thanks, Dave, for the gift of that experience. Thanks, Michael, for the lessons in fragility and beauty.

Fame Is Only The Run From Death: By Chris Braide

The older I get, the more the truth stands naked in front of me:

fame is not about love, or relevance, or artistic impact.

It is simply the most elaborate distraction from mortality ever invented.

I watch these men — men I once knew well — still performing the same gestures they perfected in their twenties, as if the performance could somehow hold back the tide of time.

The crooner singing that song from 1987, with a stage-smile that once meant something.

The New Waver, nearly 80, with a girl young enough to be his granddaughter holding the female vocal lines.

The bodies older, the voices thinner, the meaning long evaporated — and yet the show goes on.

It borders on the grotesque.

Not because they are ridiculous, but because they are terrified.

Every repetition onstage is a whispered plea:

“Not yet. Don’t let it end yet.”

As Jean-Paul Satre once said – Nothingness haunts being.

Fame becomes a sanctuary from the truth no mask can outrun.

Michael Hutchence was the exception.

He saw through the illusion.

For all the glamour, the cameras, the myth of immortality built around him — he understood its core was hollow.

He felt futility like a weight in his bones.

It wasn’t the drugs.

It wasn’t the career dip.

It was the sudden understanding that fame cannot save you from the truth:

nothing you build will stop the end from coming.

Most people in the public eye spend their entire lives running from that moment — the moment Hutchence reached.

Because fame, in its purest form, is the desperate attempt to stay alive in the minds of others.

If they still talk about me, I still exist.

If they still want me onstage, I’m not fading.

If I can keep recreating the glory of the past, perhaps the past hasn’t left.

But the truth is merciless:

fame is nothing more than the denial of death.

A shield held up against the void.

A bright light meant to blind the person holding it.

A performance that hopes to drown out the silence waiting at the end of every song.

It’s heartbreaking once you see it.

The man singing the hit he had at 22 is not celebrating the past —

he is trying to resurrect it, trying to avoid the horror of becoming a mortal, finite, ordinary man.

The stage keeps him from hearing the ticking clock.

And yet, for those of us who can feel the wind — the existential wind that whispers the truth behind everything — fame becomes almost unbearably sad to witness.

Because once you understand that life is fleeting, fragile, beautiful in its impermanence, you no longer need an audience.

You no longer need the bright lights.

You no longer need to be adored to feel real.

Those who cling to fame are not chasing glory.

They are fleeing oblivion.

Those who let life touch them — truly touch them — have no need to run.

I’d rather feel the wind.

I’d rather face the truth.

I’d rather know the emptiness and the sadness and the beauty than live behind a mask until the mask becomes the face.

Fame is the run from death.

Art is the acceptance of it.

And love — real love — is the only thing that survives it.